Eat Here!

On the semiotics of taste and the inevitability of… pizza!

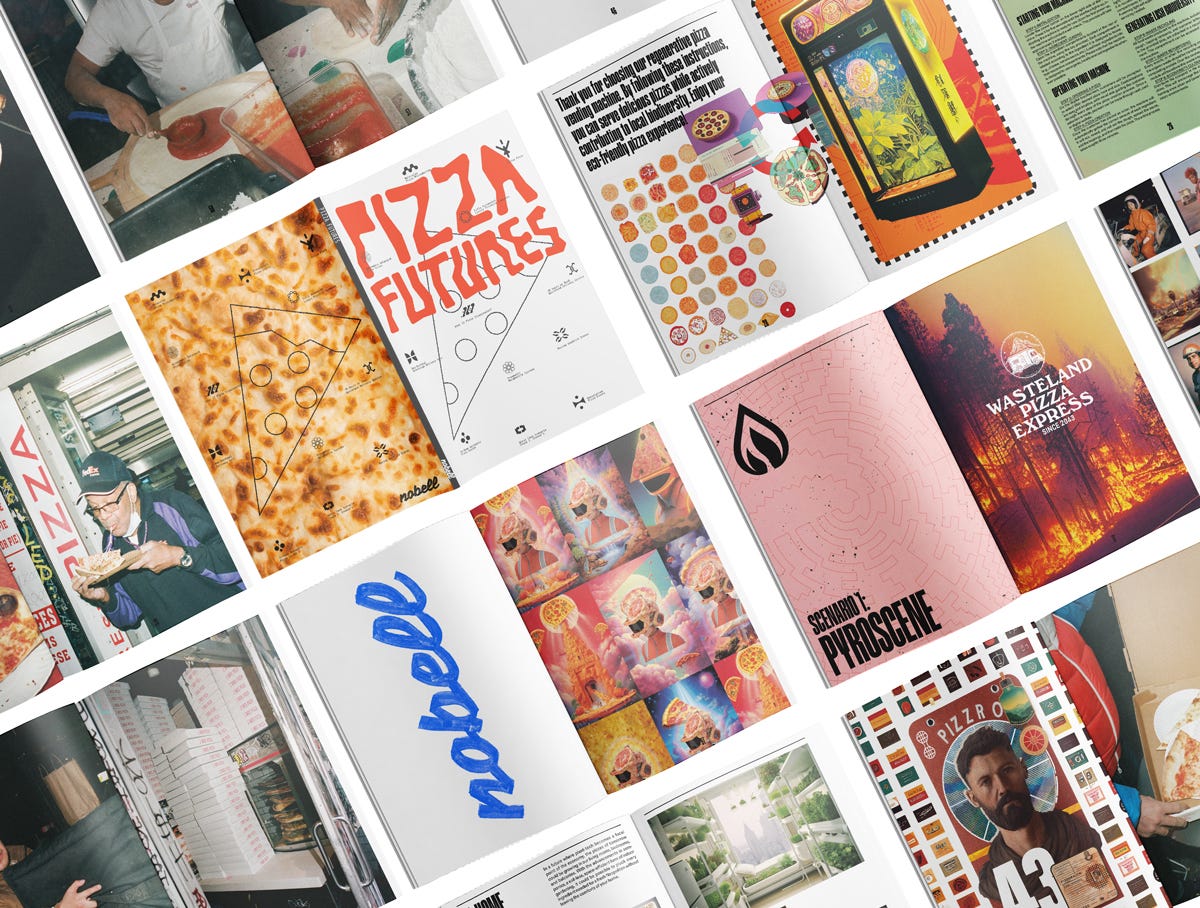

[The following in an excerpt from Pizza Futures, a forecast of pizza’s future by Nobell Foods. You can download your copy here.]

If you've read this far, you can tell that a fair bit of ink has thus been spilled on pizza. So many words communicated about such an ostensibly simple food. Odes and prophecies, diatribes and histories. Words written by avid fans, eaters, and slingers of pizza (myself included), but not by all of pizza's stakeholders. If you'll forgive me a Seussian aside, "Who speaks for the tomatoes? Or the wheat, yeast, or cheese?"

Human exceptionalism would have us think ourselves masters of communication, the sole arbiters of speech. But we're not special. The whole of the living world speaks.

To a single cell of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, endowed with chemosensitive genes to differentiate concentration gradients of simple sugars in its surroundings, an "Eat Here!" sign and the eats themselves are one and the same. (1)

In both nature and advertising, the medium IS the message. Marshall McLuhan's commentary on human artifice proposed that the communication mediums themselves, not the messages they ferry, ought to be the primary focus of our attention.

With that in mind, ask yourself the following: "what is pizza?"

Is it a convenient meal both beloved and devoured 3 BILLION times over in the US alone, every year? (2) Is it a vegetable by congressional decree? (3) Or, as Italy's national dish, is it as big a cultural export as the Beatles are to Britain? While these may all be fun musings on 'za, from McLuhan's point of view, none of them speak to the heart of the beast. What message does pizza convey? Insofar as it could be considered a medium, what is pizza a medium for?

Well, in the biological sense as a meal entire, to us humans, pizza is an energy source. But unlike wheat or yeast, planted wherever chance might find them as they wait patiently for the sun to shine or fruit to ripen, we do not passively pull pizza's chewy-greasy-crunchy nutrients through the self/world boundary of our cellular membranes.

No, we must seek out its ingredients. But beyond just a grocery list, for pizzas to exist on Earth in the billions, year after year, we must coax multiple branches of life into mutual cooperation. Luckily, we've been doing just that for some while.

All of the so-called "pristine" civilizations were founded on grain crops: Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Indus Valley, the Yellow River, the Mayans, and the Inca. Wheat, barley, millet, rice, and maize acted as both food sources both for individual laborers, but also as a currency for burgeoning societies; taxable and storable by states for redistribution in times of famine, with the surpluses helping to feed priests, craftsmen, officials, and other non-agricultural workers. (4)

But how were these botanical pillars of civilization actually consumed? Crude porridges may fill you up, but without the action of bacteria and yeasts, after some time, you might find yourself nutrient deficient, your vital organs compromised.

With the simple addition of time, the fermentation of grains and water transmutes a thick gruel into a dough that can then be baked in an oven, fried, grilled, coal-fired, or griddled. While the art and science of baking can constitute whole PhDs describing a pantheon of forms, in its essence, bread wants to be flat.

Flatbreads are the simplest, most satisfying, and most versatile type of bread. They go by dozens of names and can be found in almost every culture on Earth. They can be eaten fresh, dried and rehydrated, frozen and thawed. It's for this reason that archeologists posit that flatbread was probably firstbread.

Among the earliest evidence for it were crumbs found at a site in Jordan dating back to 12,400 BCE, predating widespread agriculture in the region. (5) With this knowledge in hand, if you afford yourself the right historical perspective shift, there's an angle through which we can view flatbread—a triumvirate pact between grasses, fungi, and humankind—as a requisite preadaptation for the ecological evolution of a clever ape and its interspecies consorts, into a eusocial, planet-shaping force majeure.

For at least 14,000 years, we've been milling, mixing, kneading, yeasting, pulling, rolling, and cooking flatbreads into existence, all to the great satisfaction of our own tastes but also to the tastes of the grains and yeast used in the recipes. (Does a blade of grass not yearn for unfettered sunlight? Do ascomycete cells not bubble with effervescent excitation when well fed?)

To be sure, not Delicio, nor Chicago deep dish, nor even pizza napolitana, have been around anywhere near that long. The medieval Latin Pizze first pops up in the historical record in the "Codex Diplomaticus Cajtanus" in 997 CE. As a dish, it would have been more similar to a round focaccia, baked with toppings, than the pizza we know today.

The roots of its name are thought to be linked to the Greco-Assyrian pitas Gaetanean archbishops would have been well acquainted with through Mediterranean trade. Before them, North African Bedouins had their own name for it. Which is the point. Whatever you call it, as long as there has been flatbread, people have been enjoying it doused in toppings.

As a child, home from school, I'd make pizza out of bagels, Triscuit crackers, or even English muffins. As an adult, I've slow-fermented rare, imported flours, caught wild yeast on the wind for sourdough, and labored for days over Chad Robertson's recipe. But whatever route I've taken, in the end, it's always been deeply satisfying. A perfect meal. Not just as a biochemical energy source to keep my cells dividing but as thousands of years of human culinary history, refined, honed, and distilled.

Flatbreads, while delicious on their own, are the original medium for the message of flavor. So perfect a vessel could have only been born out of the needs of prehistoric man. Requiring so little to craft, (you could not strip anything away to make it simpler) yet it gives back so much. It is the meal, and the plate, begging to be adorned by whatever preserved meats, cheeses, greens, oils, or sauces one might have on hand. It is both the medium and the message, no cutlery required.

In his work, Swedish food historian Richard Tellström writes of "taste chords." As an idea, taste chords constitute the harmony that comes from several flavors that, like the standing waves of plucked guitar strings, resonate to live for a very, very, long time should they carry sufficient importance to the cultures that produce them.

Language resonates in the same way. The Proto-Indo-European root word for bread—bhreu—dates back some 6000 years. Over that time, it's traveled through dozens of tongues and billions of mouths to today, all the while remaining largely steadfast. And that's because its meaning "to bubble, effervesce, char, and burn" is still as important to us now as it was to the ancients.

Fermentation and cooking are still as important to us now as they were to the ancients. We don't know what the prehistoric Jordanians called their flatbreads. But we know they loved them, because we still love them.

What is pizza today could be called something else tomorrow, but it will still have a tomorrow. The fidelity of humanity's longest-standing recipes transcends the words we use to describe them, because such recipes don't belong to humanity alone. Grasses and fungi (not to mention tomatoes and cows) are as invested in the delicious medium of flatbreads as we are, because it's their medium, their message too. "EAT HERE! EAT US!" Whatever the world looks like 14,000 years from now, assuming there are still beings capable of crafting recipes, then "pizza" will still be on the menu.

[1]

Sugar Sensing and Signaling in Plants

Filip Rolland, Brandon Moore, Jen Sheen

The Plant Cell, May 2002

[2]

We eat 100 acres of pizza a day in the U.S.

Lenny Bernstein, Washington Post, 2015

[3]

Is pizza a vegetable? Well, Congress says so

Lizz Winstead, The Guardian 2011

[4]

Against The Grain

James C. Scott, 2017

[5]

Stone Age Bread Predates Farming

Barras, New Scientist, 2018

David Zilber is a Chef, a Fermenter, a Food Scientist at Chr. Hansen, and the Bestselling Author of The Noma Guide to Fermentation.